Mind Wide Open Episode 28 with Gary Gulman

Guest Bio

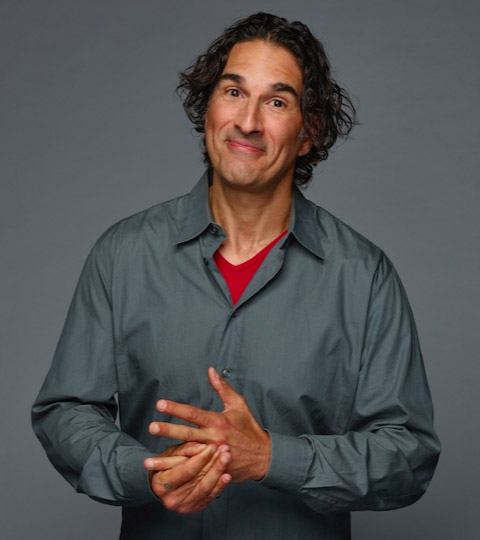

Gary Gulman

Twitter @GaryGulman

IG @GaryGulman

Over 25 years in comedy, Gary Gulman has established himself as an eminent performer and peerless writer. His most recent standup special for HBO, “The Great Depresh,” is a universally acclaimed, tour de force look at mental illness, equal parts hilarious and inspiring.

A product of Boston, Gulman has been a scholarship college football player, an accountant, and a high school teacher. He has made countless television appearances as both a comedian and an actor.

He is currently writing a memoir for Flatiron Books, tentatively titled “K Through 12.”

Transcript

Gary Gulman: You tend to blame yourself, “If I were stronger, if I was smarter, if I were tougher, if I were making more money”, but it has nothing to do with that. It’s chemistry.

[music]

Lily Cornell Silver: I am Lily Cornell Silver, and welcome to Mind Wide Open, my mental health focused interview series. Today, I am talking to comedian Gary Gulman, who has an incredible HBO special called The Great Depresh, all about his struggles with severe depression. Today he and I are talking about his experiences being hospitalized for depression, the importance of talking about your own mental health, and how he has infused that into comedy. Thank you so much for watching, and I hope you enjoy.

Lily: Hi, Gary. Thank you so much for being here. I’m sure everyone that you’ve ever talked to has said this to you, but The Great Depresh, incredible.

Gary: Thank you.

Lily: Your ability to talk about mental health in a form that is so real, and doesn’t undermine any of the honesty of the pain you’ve experienced, but still allows others to relate to it, is so admirable, and something that I hope to achieve one day, so amazing. Thank you.

Gary: The thing is, when I was your age, I was suffering from depression and I told no one. I used to sneak into my therapist’s office at the college. The good thing is that you are coming of age at a time when people are talking about it in full voice, not whispering about it, or sharing secrets about it, or feeling hopeless about it. I say this a lot, there has never been a better time to be mentally ill.

Lily: [laughs] Honestly, that’s super true. I talked about this in an interview I did with some of my friends that I grew up with, and something that we talked about was like, in third grade, second grade, our parents had us all in therapy and none of us told each other. We were all telling our therapist as kids, like “None of my friends are in therapy, I’m weird. I’m crazy.” Now that we’re older and we’ve talked about it, we found out that we were all at therapy, some of us even had the same therapists. You’re so right, that’s something that my friends and I talk about.

Gary: It’s really fantastic. There were so many reasons why couldn’t have done it even five years ago. One of them was just I wasn’t well, but the other thing was that I didn’t really have an audience that I felt would go along with me in this departure from what I usually do. Because my act was rather tame with respect to the darkness of it. I didn’t get very dark. I don’t mean to say that the depression, I got very dark, but the subject tends to be something that people feel uncomfortable around.

I was very fortunate. I had that audience that was so generous with their hearts and their time, and were patient with me while I was practicing it and trying things out. I couldn’t have done it without them, honestly.

Lily: Right. Something that I’ve experienced in doing this series is the realization of how much people want to talk about it. People are so dehydrated for these conversations. I’m glad you experienced the same thing. That it’s something that people really are wanting to talk about. They want to hear other people’s stories. They want to hear your story. They want to share their story with you. I think that’s good news.

Gary: I think that’s something you’ll notice over and over again, is that this thing you were so worried people would judge you on or dismiss you, or be concerned with working with you. It’s just the opposite. It allows them to share their stories and their pain, and it brings you closer with them.

I’ll give you an example, a man during the show started fumbling around and talking to people around, and he said, “What is this for you, therapy?” The rest of the audience were so alarmed by that and were so thrown by that, that they cheered me when he left. I said, “The name of the show is The Great Depresh, I guess that was confusing to you.” But it was worth him doing that just because the people showed me how much they cared for me. It was really nice.

I think all the things that I feared about letting my manager and other people I worked with know about these things. I didn’t say all of it at once. I told them I was depressed, and then later on, I told them that I was checking into the hospital, and then even later than that, I told him what kind of treatment I had which was– I thought people would be horrified when I told them that I had electroconvulsive therapy, and it turns out they didn’t bat an eye, and they thought it was interesting. Just that they thought it was something that people would get some use from hearing about somebody else, especially other people who’ve done it and didn’t feel they could share it.

Lily: Exactly.

Gary: It’s so helpful.

Lily: Would you say that the answer to him about, “Is this show like therapy for you?”? It seems like the answer might be yes. Like, “Yes, it is a form of therapy”.

Gary: It is therapy and it was, especially at the beginning when I first started just telling a few stories at very small venues, maybe less than 30 people in the audience. I found that getting out of the house and being around other comedians, and then having this adrenaline flow when you get on stage, that was immensely therapeutic.

There was a time when going up and doing the shows was very painful and it wasn’t helping, it wasn’t beneficial, and one of the reasons was that my performance would dictate my mood, so that if I had a bad show, I couldn’t get out of bed the next day.

Lily: That sounds very familiar growing up in a music environment. That sounds very familiar.

Gary: Yes, and that is for somebody who works every night, it’s like, there’s a referendum on your worth every night. And that is unhealthy, and it’s not safe for me. I just happened to be reading an article about this author that I really liked, and it was his notebook. In the notebook, he had taped a quote, I could barely make out the quote, but it was this, “Ever tried, ever failed. No matter, try again, fail again, fail better”, and fail better became my motto, my mantra.

It was miraculous because it freed me from all the pressure and the fear of, “Okay, if it goes well, I’ll feel good about myself. And if it doesn’t, I’ll be inconsolable.” Once I was able to deal with that– and it’s a lesson that I should have learned as a child, but I– I don’t know how I didn’t figure out that it was OK to fail and crucial to growing as a person and as an artist.

Lily: I think being in the public eye is different ballgame in that, like the failure feels like it has a higher stake, maybe.

Gary: Yeah. It was hard enough just to talk about this stuff without also having to be perfect about it, and super funny every time. Once I was able to give myself that permission, it wasn’t smooth sailing as if I wrote everything in a day, it was just that every show, there were steaks I wanted to do well, but the stakes weren’t my life and, and my happiness. I still get bummed out if I have a bad show, but I also can look at it as something that was actually moving me forward.

Lily: Definitely. And fail is a strong word. I think that we take the word ‘fail’ too lightly.

Gary: That’s a great point. Maybe I use it so frequently because I’ve repurposed it for taking a risk, and then not nailing it.

Lily: People that I’ve talked to it’s gotten to a point where, especially for our generation and the generation above me, it’s like, we either continue the stigma and don’t talk about it, and literally die or go crazy, or we talk about it. The options have become limited, limited, limited, like, “Okay, we need to talk about this. This needs to be talked about”.

Gary: Not talking about it didn’t work at all.

Lily: We learned by example. Right? [laughs]

Gary: Yes. I was 19 when I first went to a therapist, and once I had a name for it and I understood, it didn’t wipe out all the blame. That’s some of the worst parts about this type of thing is that you tend to blame yourself, “If I was stronger, if I was smarter, if I were tougher, if I were making more money”, but it has nothing to do with that. It’s chemistry. I remember I used to walk to my therapist and there was a huge– it was just painted on a building. It was an advertisement, it wasn’t a billboard, it was literally painted on a building. It said that mental illness is not a character flaw. I would read it every day and I would think to myself, “Well, it is my case. If I were stronger and if I were tougher, I could fight my way through this”.

Now on the other side of that is somebody in his right mind, I can say, “No, that’s exactly right. It’s not a character flaw.” It’s so sad that the very thing we need to get out of it is the thing that’s attacking us, and telling us we can’t. It’s crazy.

Lily: Right. Something that you’ve talked about is that, the feeling that the real version of you and then the version of you that others perceive, there’s such a gap between those two things. For me, in my struggles with grief, anxiety, and with my own depression, that has been the major cause of isolation for me, or the feeling of isolation that people see me as very happy, positive, and bubbly. I struggled greatly with trying to convey this other side of me that I’m the only one that knows what that’s like. So I’m curious to hear your experiences with that, and if that caused a sense of isolation for you.

Gary: When people think you have a perfect life and you tell them that your life is not perfect. I think– not that they’re glad, but just to know that you’re not perfect and that you have your struggles makes you more human. I think that’s where a connection is strengthened there. And there will be people who say, “Listen, I don’t want to hear complaints from somebody who is doing better than me, I just can’t handle it.” And that’s fine. I’ve had that too, and it’s sad, and it’s unfortunate, but for the most part, with only a few exceptions, people are very happy to help. It strengthens the relationship. I’m not sure if I answered your question.

Lily: Absolutely. I think that’s something that I talk about a lot in this series, is mental health being a unifying thing in the sense that everyone experiences it at some point. Even if you’re someone who doesn’t struggle with things, where it’s at the forefront of your being, in the forefront of your life, you know, somebody who has. I think that’s so important. That’s where so much of the stigma needs to be shed, is around the fact that we feel like we can’t talk about it with other people, or even view it as complaining.

Gary: I had the worst depressive episode of my life from 2015 until near the end of 2017. It was reasonable that I would be hospitalized. There were several other depressive episodes that I had in my life where it didn’t get to that level. At no point where I say, “I need to be in the hospital, I need to have some serious treatment and I can’t take care of myself.” It wasn’t a fun time. I was depressed. It was just low grade and everything I was doing was very difficult. The exercising that was supposed to make me feel better was so difficult-

Lily: – and the last thing you want to do. The absolute last thing.

Gary: Yes. Even just keeping up with my wife, who’s, I think she’s 5’11. I’m 6 ft. She’s about seven inches shorter than me, keeping up with her walking was difficult. There are physical components to depression that people either don’t mention because they feel so lousy, or they think are just them, but they’re a part of the chemistry. It slows down your thinking, it slows down your walking.

The thing that I am concerned a little bit about is that people will think that they can’t share their tough times with me because it doesn’t rise the level of checking yourself into a hospital. I want them to be able to say, “I’m having a really hard time getting out of bed, I’m having a really hard time enjoying something.” This is something that people don’t even bother complaining about. But “These things that I used to enjoy, are no longer bringing me any pleasure and fun.” That’s what life is, is the things that bring you enjoyment that you look forward to. If those things aren’t working, then it’s something that needs to be addressed. We get used to this feeling where we think just not wanting to quit my life and stay in bed all day is good enough. I don’t want to push for more, and I don’t want to upset the apple cart…

How does “upset the apple cart” expression, still work today? It has no meaning at all. There’s no apple cart that people are concerned about. Apple could sell them just a cart full of apples, but anyhow, whoever made the expression is really doing some overtime. The point is that you’re satisfied with a very unsatisfactory situation just because it couldn’t be much worse or it has gotten worse and you just settle, and it’s sad. I feel bad. I want people to thrive.

Lily: Definitely. That’s a conversation I’ve had with friends many, many times, especially when, if I’m in a period of struggling and whoever I’m talking to is as well, that idea of how are you feeling, like what’s going on. They say, “I don’t want to die, it’s a really good day.” I’m like, “When did the bar get that low?” When did we decide that that’s okay? It’s okay for me to be surviving in that way, and that I don’t deserve to do something to make my life feel better and make me want to live my life in a fuller way.

Gary: Upset the apple cart is what I’m saying. You got to get out there and upset that apple cart.

Lily: You need to make t-shirts with that on it. “Wait, upset the apple cart.” Something else that I was super curious to hear from you about is like in interpersonal relationships, you mentioned your wife, and I think a common theme for people that struggle with mental health and being in relationships is feeling like they’re a burden, and that’s something I’ve absolutely experienced, is like how do I take care of myself when I’m barely able to do that and still have the energy to be pleasant to be in a relationship with? That’s something I’m curious if you’ve experienced that.

Gary: I’m so glad you asked about this because I always try to get across what a team effort it was for me to get better and how my wife Sadé—not THE Sadé, by the way.

Lily: I was gonna say, dang!

Gary: Right, it’s a Sadé. I can’t stress enough how helpful it was to have somebody who was in it with me, not to say that it’s somebody who’s not in it, who’s not worth being with, it’s not for everybody, but I think it really helped my cause along to have somebody who went to every psychiatry appointment with me and who did reading on the side to figure out if there were new studies, she would bring up these new studies with the doctor, and that was another case where the doctor wasn’t arrogant and said, “How dare you question my-? I’m a doctor, what do you think that diploma means up there?”

He would say, “That is a promising area, we can look into that.” Or he would say, “That’s actually not something that would be beneficial for Gary at this point.” He never made her feel uncomfortable. He took it in such a humble manner, and she did really good research. She actually, and I think the statute of limitations hopefully will have run out on this, but she grew mushrooms, psilocybin mushrooms in our apartment because she had read a study that is actually incredibly promising and has really done great things for people about the effects of microdosing mushrooms, the psilocybin. I think it is, although I don’t know mushrooms. I was always afraid that if I took mushrooms, I would have a trip that I never came back from. I was very careful about that.

Lily: I get anxiety taking melatonin, so I get you, I can’t do anything [laughter]

Gary: But what I was was going to say that it’s important, but when you get into a new relationship and you think it’s going somewhere, I always told the people, “I have a history of severe depression and it gets dark. If you want to bail, now, I would completely understand.” So she knew that I had this propensity, but six months later, this started and she stuck with me, and I’m grateful because, like you said, there was part of me that felt like I was a burden and I would have completely understood if she left me because nobody signs up for what I was going through, and I’m not sure I would have been as strong as she was. It was valiant.

Lily: That’s beautiful. I think there’s so much to be said about having that as a prerequisite conversation because, I’m very young, but I’ve been with someone who really doesn’t understand mental health and that’s not part of what they could like conceive as being part of a relationship. And I’ve been with someone who’s like, “Yeah, I totally know what that is.” To have that understanding and to have that willingness to go the extra mile to really try to understand it makes such a difference.

Gary: I think the one thing that I can say for people who have had mental health issues is that we’re pretty good partners when we’re well. I don’t know if there’s any proof of this, but I want to say we’re more empathic or more understanding, we at least get it. We’re much less likely to judge you or at least have any standing to judge you, how dare we judge anybody else for their issues.

Lily: This is a 180, but I’m curious if you agree with the idea that comedians are all a little bit off, or comedians all have struggled with mental health and that’s a thing, because that’s something that is in a through-line in so many comedians’ lives and so many of their acts. Do you feel like that’s true? Do you feel like that included facing your own state of mind ever?

Gary: There’s something in art and, especially in art criticism where things are given more weight because they’re bleak, or nihilistic, or pessimistic.

Lily: The whole Seattle grunge movement. Yes.

[laughter]

Gary: That can’t be the case all the time for everything, there needs to be a balance. It’s radical to be hopeful now, it’s radical to be optimistic. I think that it’s the easier story to tell that we’re all doomed and we’ll never get out of this, but I think it’s, one, we can’t predict the future. Two, on the way to the future, I find myself feeling a little bit more energy when I think, “I’ll figure it out. We’ll figure it out.” We’ve overcome a lot of bad things. I just know that there are people who hear somebody interviewed about depression and they think, “But that’s you.” And I used to say that the same thing, and the one thing I will say is that I was hopeless too, and I really didn’t think was anything that was going to save me.

I didn’t think that I would do comedy again. I was spending a lot of time thinking really scary thoughts. I don’t think it’s brave what I did on depression, because I was so thrilled to be alive and thriving that I wanted to share it with anybody. What I really look to is to say how brave the people are, who are struggling with it, who are getting out of bed every day and are fighting. I hope they know that they deserve a medal for that because it’s really hard, just getting out of bed is a real victory some days. I used to say, “Just get out of bed for a half-hour. If you want to go back to bed, go back to bed.” But believe me, that half-hour makes a difference, and sometimes a donut.

Lily: Well on that perfect note, thank you so much for being here, Gary.

Gary: It was a pleasure. We’ll have to do it again, in person, maybe, or something next year because it’s delightful talking to you, and I feel that you may be an antidepressant yourself.

Lily: [laughs] Thank you. Thank you so much.

[music]