Guest Bio

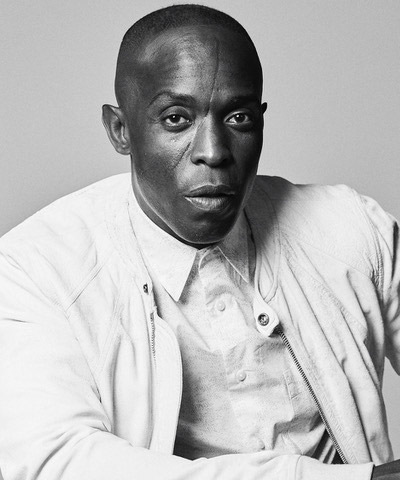

Michael Kenneth Williams

Michael Kenneth Williams is one of this generation’s most respected and acclaimed actors. By bringing complicated and charismatic characters to life — often with surprising tenderness — Williams has established himself as a gifted and versatile performer with a unique ability to mesmerize audiences with his stunning character portrayals.

Williams is best known for his remarkable work on THE WIRE. The wit and humor that Williams brought to Omar, the whistle-happy, profanity-averse, drug dealer-robbing stickup man, earned him high praise and made Omar one of television’s most memorable characters.

Williams also co-starred in HBO’s critically acclaimed series BOARDWALK EMPIRE in which he played Chalky White, a 1920’s bootlegger; and the impeccably suited, veritable mayor of Atlantic City’s African-American community. In 2012, BOARDWALK EMPIRE won a Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series.

Williams received his first Emmy nomination for Outstanding Supporting Actor for HBO’s BESSIE and subsequently received his second Emmy nomination his work in HBO’s highly acclaimed limited series THE NIGHT OF.

His recent projects include Ava DuVernay’s Netflix miniseries WHEN THEY SEE US, which tells the heartbreaking story of the Central Park Five and which garnered Michael his third Emmy nomination as an actor. Williams recently wrapped the highly anticipated HBO series LOVECRAFT COUNTRY from producers JJ Abrams and Jordan Peele. Previous TV credits include Sundance Channel’s HAP & LEONARD, the ABC limited series WHEN WE RISE from Dustin Lance Black and Gus Van Sant and the IFC comedy mini-series THE SPOILS OF DYING.

Williams made his feature film debut in the urban drama BULLET after being discovered by the late Tupac Shakur. Previous feature film credits include Ghostbusters, Assassin’s Creed, Bringing Out the Dead, 12 Years A Slave, The Road, Gone Baby Gone, Life During Wartime, Brooklyn’s Finest, The Purge: Anarchy, Kill The Messenger, Inherent Vice, THE GAMBLER, MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN, and the John Leguizamo directed independent film CRITICAL THINKING, which will premiere later this year at SXSW.

Giving back to the community plays an important role in Williams’ off-camera life. He recently launched MAKING KIDS WIN (MKW), a charitable organization whose primary objective is to build community centers in urban neighborhoods that are in need of safe spaces for children to learn and play. Williams currently serves as the ACLUs ambassador of Smart Justice, and as an ambassador for the INNOCENCE PROJECT, while serving on the board for NY based organization URBAN ARTS PARTNERSHIP.

Williams served as the investigative journalist and executive producer for Viceland’s BLACK MARKET, a documentary program that exposes and comments on illegal markets throughout the world with a focus on the people involved and connecting with them on a human level.

In 2018, VICE returned for its sixth season with an extended special season premiere featuring Williams as he embarked on a personal journey to expose the root of the American mass incarceration crisis: the juvenile justice system. RASIED IN THE SYSTEM offered a frank and unflinching look at those caught up the system, exploring why the country’s mass incarceration problem cannot be fixed without first addressing the juvenile justice problem. Williams investigates the solutions local communities are employing that are resulting in drastic drops in both crime and incarceration. Michael’s work on the spectacular documentary earned Michael is first Emmy nomination as a producer.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, Williams began his career as a performer by dancing professionally at age 22. After numerous appearances in music videos and as a background dancer on concert tours for Madonna and George Michael, Williams decided to seriously pursue acting. He participated in several productions of the La MaMA Experimental Theatre, the prestigious National Black Theatre Company and the Theater for a New Generation directed by Mel Williams.

Michael Kenneth Williams resides in Brooklyn, New York.

ALL donations will be used to pay young people most impacted by gun violence, over-policing and Covid-19. https://charity.gofundme.com/o/en/campaign/crew-count

Below are links to Mike’s activism:

#WeBuildTheBlock Social Justice Dinners

Mental Health Retreat with Young Women

Summer Youth Employment: Project LEAD

Transcript

Michael K. Williams: It’s imperative that we start to allow space for our young people to one, recognize that nothing about systemic racism is normal, and then, the trauma that comes from that is not normal. It’s okay to say that we’re hurting and it’s okay to ask for help.

[music]

Lily Cornell Silver: Hi, everyone, I’m Lily Cornell Silver. Welcome to Mind Wide Open, my mental health focused interview series. Today I am talking to actor, activist, and artist, Michael K. Williams about the mental health of youth of color, race-based traumatic stress and intergenerational trauma.

Additionally, with today being Dr. Martin Luther King Day and a day of activism, we are talking about an initiative that Michael is part of called Crew Count, which works to protect the community’s most disenfranchised and marginalized members from being criminalized without constitutional cause by engaging them into the voting process, while also addressing food insecurity, and gun violence.

I am going to be putting the link to the GoFundMe for Crew Count in my bio, so please donate if you’re able. Thank you so much for watching, and I hope you enjoy. Hi, how are you, Michael?

Michael: Fine. Yourself? Happy holidays.

Lily: Thank you, you too. First and foremost, I just want to say thank you so much for being here, you and your work exemplifies the mission of Mind Wide Open to a tee in bringing awareness to and fighting for systemic change, and especially the mental health and wellbeing of marginalized communities and youth of color. It’s an honor to have you here. Thank you so much.

Michael: Thank you.

Lily: One of your latest projects around social justice is the Crew Count initiative. Could you describe, in your own words, what that is?

Michael: Yes, ma’am. During the Bloomberg administration, a program was implemented called Operation Crew Count. What that did was, that expanded the gang database up to like 40,000 names, unbeknownst to the people who were actually on the list. Say, for instance, if you were visiting your grandmother, who happened to live in my building, and if I was a gang member, and you happened to be stopped and frisked, which if you were a Black male, was like a 99% chance that would happen, you would then be put on that list on a gang database list, then they would survey you.

Dana, came up with this great idea to counteract that. We started a program called Operation Crew Count. What we thought would be brilliant is if we went to the same blocks on the same communities that were being targeted for this gang database, and registered and got the youth from that block to get activated and to register their own block, how powerful and how beautiful would that be.

That’s pretty much the basis, we get the youth from the community, we give them a budget, we hire them, and then we give them a budget to hire DJs. They hired a marching band, the Empire Marching Band from Brooklyn, they buy the food, they have one of the parents of the youth, he comes around with his huge jerk barrel, like a jerk chicken oven, and they cook out on the street. We hire DJs. It’s a beautiful thing.

While we’re having all this fun, they are at a table registering the community to get counted on the census, and to be registered voters. We started it for the census, and the presidential election which just passed. We thought it was important for New York City to keep the momentum going straight up into the mayoral election in 2021 of June.

Lily: That’s beautiful. That’s incredible. That idea of occupying the space and that boots on the ground work is so amazing. Thank you for doing that.

Michael: Thank you for thanking me, but there’s no need to thank me. I’m doing nothing special. I’m only doing what I’m supposed to be doing. I’m from these communities. I don’t like that narrative of putting me on the pedestal like I’m doing this nice thing for the children. No no no.

You’re right, it is a beautiful thing. Not because I’m there, not for anything that I’m doing, it’s beautiful because to watch the light go on in these youths, these young people’s eyes, and to feel them inspired, to feel them empowered, to see them feeling empowered, that’s where the beauty is.

My favorite thing, besides the food, is watching the Empire Marching Band. They drive me every time to see these young men and women from the community playing live music in the street. It’s surreal. That’s the best that makes it beautiful. I’m just doing what I’m supposed to be doing, as a member of my community.

Lily: Absolutely. Speaking with Dana, she talked about how youth of color, and especially youth of color living in poverty, you have higher rates of PTSD than even soldiers returning from war. Could you expand on that?

Michael: Yes. As a middle-aged man, myself, I have just come to the realization of how much trauma I have, unresolved trauma, unrecognized trauma, much less unresolved. I’m in therapy right now for it. I’m starting to unpack all the systemic racism that I deem normal, that normalized from my childhood up until me now as a grown man. I see the same things affecting the youth in the same community that I’m from.

It’s imperative that we start to allow space for our young people to want to recognize that nothing about systemic racism is normal, and the trauma that comes from that is not normal. It’s okay to say that we’re hurting, and it’s okay to ask for help. That’s the narrative that we are in the space that we are creating for our young people in the community to spot and recognize our trauma, and then to start to resolve it by doing things that are esteemable, things that are impactful, things that are empowering, like build a block campaign.

Hurt people, hurt people. The amount of violence that’s inflicted on young people from the same communities, that is just something wrong with that, what makes a young person want to kill someone that looks like them that comes from their community? What makes them hate someone that looks like them that comes from their community?

All of that is trauma-based action, that I’m starting to even unpack in my life, the things that have my knee jerk reactions to it. If I’m still having it as a grown man, I can only imagine the effects that that has on an adolescent mind, on a young adult mind. We’re starting to just unpack where the violence comes from, where does the notion, what is driving the violence, the anger in the community? That’s where we’re at with it right now.

Lily: Absolutely. A big thing that I’ve talked about with guests often on the show is that of intergenerational trauma, especially in the Black community and how that affects mental health today, do you feel like that’s affected you?

Michael: Absolutely. I’m starting to realize this is nothing new. My mother had trauma. I recently read something online. My mother’s Caribbean, I’m a first-generation immigrant, a child of an immigrant mom, and she’s from the Bahamas. I read something online about where the severe beatings came from, the beatings that I endured as a youth from my mother.

That came from her childhood, it’s generational, this thing about—it’s from slavery, basically, these violent beatings. When she was a woman, that got passed on to me when I was in her womb, and the thing of, I understand now where the impact from these beatings came from, out of fear, she didn’t want me to get in trouble. She’d rather her beat me than the man beat me, or get beat by the system. I was always beat as a way to be made to be good. It had its good impact on me and it also had its negative impact on me. I had to unpack that, now, as an adult.

Lily: A huge part of that, obviously, has to come from like systemic change, but how do you feel like you’re unpacking that on a personal level?

Michael: Number one, I have therapy. I have therapy every day. In fact, I started to set aside one day of the week, and today is supposed to be my day and I’m working like a crazy person, but I call it mean Mondays. Mondays are my day to reflect on what happened the previous week, what my goals are for the week in front of me. I have my therapy sessions on Mondays, and I am starting to talk about the uncomfortable things that happened to me, like my addiction, I’m a survivor of molestation, the abuse that came from the community to me. You know, dark skin wasn’t in when I was a kid, and all the things that I picked up along the way, all the baggage, the luggage that I picked up along the way that I thought was normal, I’m starting to unpack that now through therapy and just through conversations with the people in my life, I make that a part of my conversation now, when people ask me how am I doing.

Lily: Right. Thank you for saying that, because that’s a huge part of the whole series for me, is a big step towards de-stigmatizing mental health, and de-stigmatizing addiction, de-stigmatizing intergenerational trauma is talking about it, not just in settings like these, or just in therapy, but with your family, with your friends, through things like Crew Count. Yes, I’m so glad that it’s something that is being talked about in your circles.

Michael: Thank you.

Lily: I’ve also read about your involvement from Dana, as well, in mental health for young Black women, could you speak to the importance of that as well?

Michael: I’ve recently started to realize just how severely marginalized women of color are. I started with my job, at the job that I did last year on HBO. One of the character storylines is a Black woman, and I just saw my mom in her, and it’s just like, wow, women of color, Black women, hispanic women, just women of color, period, they’re the bottom of the barrel, we think of them the last, and I’m just starting to unpack what that means and their role in the community. I’ll never forget one time Dana and I went to Brownsville to visit the 73rd precinct to do some work there. It hit me like, “Wow, Mike, you haven’t been home in a long time,” like a couple of decades, when I mean home, I mean being tangible to the community, being tethered to something positive in the community. I have never really made my presence known since I was spared my drug addiction and given a second lease on life, I just took off for the races and it hit me.

I left my children alone, at home to be raised by the women in the community and the local police department. That was just on me, not saying other men, but that was me. I left my presence, I didn’t have enough presence in my children’s life. When I say my children, I subscribed to the village concept. All the kids in the community, then my little brothers and sisters and then my kids, and that’s a lot on the Black woman. She’s working two and three jobs to put food on the table, just to pay the rent, trying to raise these, like Tupac said, trying to raise two bad kids on her own. It’s not fair, it’s not fair. Then they have to be there for us. I’m starting to unpack us as men, when I say that, I’m starting to unpack women who are incarcerated.

Jesus Christ, how forgotten is the female population of women of color in the penal system? We always see women, when I used to go visit my nephew, Dominic, 90% of the bus that we would ride upstate to New York to on was 90% were female, female passengers going to see their man or their sons, just the men in their lives. You can count the men on that bus going to see their female counterparts. When women go to prison, that we forget about them, and they’re left there to deal with all sorts of abuse. I’m just starting to unpack that and to be more verbal about the importance of lifting up our women in our communities.

Lily: On the theme of mass incarceration, that’s something that I’ve studied a lot and read about a lot. I’ve read a lot of Angela Davis, but that mass incarceration and especially the disproportionate incarceration of people of color is huge and obviously has a huge effect on mental health. I’m wondering, in your opinion, where you feel like those mental health issues and mental health concerns should be addressed?

Michael: It starts with, like you said earlier, talking about it, and we have to change some things. Some distant policies need to change. We need to be more vocal about policies that speak to female issues. I can’t take seeing women on the street homeless with the kids, it tears my gut up on the inside. Right now, I think it’s still illegal to shackle a pregnant woman in prison while she’s in labor. These are things that need to stop, that need to change. We need to have more systems, more programs and policies in place that support female mental health, female issues. I don’t have all the answers, but I know it starts with the conversation, and we need to stop some things and some things need to be changed, that’s for sure.

Lily: Absolutely, yes. The policy changes, and, yes, implementing programs, absolutely, and that’s something that I live in Seattle and something that I’ve seen. Some steps towards, in the last three, four or five months is taking police funding and putting that into social services, putting that into mental health programs.

Michael: I love that you said that, and I’m glad you said that because, let’s be clear, we need good policing. I am not team abolish the police department. I’m not down with that. We need good policing in our communities, in all of our communities. However, we also need other programs, too. It’s unfair to put everything that is wrong in my community, on the desk of our local police department. That is unfair to us and it’s unfair to them. They don’t have all that training. They are not equipped or trained to deal with mental health issues. Nor should they be called for because my kid is making noise in the hallway or my kid is smoking a little weed on the staircase, I’ll tell you, those are quality of life issues, and I believe if we took some of the resources, some of the funding that we give to all the police departments, just take some of it and reallocate it, is what you just explained. It’s not about defunding, it’s more about reallocating some of the funds that were given to them to create programs, to help them help us. What you just said was brilliant and I just wanted to acknowledge to that.

Lily: Thank you. It’s something that Seattle is actively doing, and Minneapolis we’ve seen is actively doing, and I think that’s amazing and speaks to exactly what you were saying about policy changes and implementing mental health services, especially for youth of color, especially for women of color. Since today is Dr. Martin Luther King day, can you talk a little bit about what this day means to you, in terms of activism and social justice?

Michael: Yes. When I think about Dr. Martin Luther King, I forget just how young he was when he left us, 30 something years old, in his young 30s, I think he was 32, and he accomplished more with his life, in his 32 years, than most of us do with our entire lives. I love the fact that he spoke for all races, although, it was the civil rights issue that was at his core of his legacy. That was for all rights and for all human beings. I believe he became dangerous when he started talking about uniting all races, the common man, that we were all one, I think that’s what made him dangerous to the powers that be, who liked to keep us separate and divided.

Sometimes I look at what he stood for and all that he accomplished, and when I look at today, it’s very easy for me to get discouraged and to think, “Well, what has changed from the days when Dr. King walked the earth till now?” It’s very easy for me to say what has changed, but the fact that you and I are sitting here, right now, having this conversation, white woman, Black man, talking about unity and things in the community, that’s proof that we are going in the right direction. Are we there yet? No, but we’re definitely moving in the right direction. I believe that that’s what he stood for, working hard, working to help people, not being afraid. I look, I think back at how fearless he must have been in the face of all that adversity, if I could just have an ounce of that right now, I’m ahead of the game. He’s definitely one of our heroes.

Lily: In a similar vein, my last question for you is what is something that’s giving you hope right now?

Michael: The main thing that gives me hope, right now, is the youth, that Dana and I are so fortunate to be around, to see them smile through all their pain, through all their trauma, to see little flickers of hope in their eyes of aspirations of wanting to be better, or the way they see themselves, to hear them talk about their dreams for the future gives me hope. It gives me hope. I’m a sucker for the youth, and to see them– I tell them, “Don’t follow me, tell me where we’re going. You take the wheel.” I love seeing them feeling empowered, I love seeing them dreaming, I love seeing them feeling hopeful. That’s where I get my hope from for the future.

Lily: Amazing. Well, thank you so much for being here, Michael. It’s truly an honor to speak to you, and I hope our paths cross again sometime. [laughs]

Michael: I’m sure it will. [laughs]

Lily: Have a good therapy session, first and foremost. [laughs]

Michael: Thank you. Mean Mondays. Everybody, get a mean Monday going on!

[music playing]

[00:21:09] [END OF AUDIO]